Research study and recommendations to ensure the effective treatment and supervision of juveniles adjudicated delinquent for a sex offense

Recommendation to extend Juvenile Court jurisdiction to include 17-year-olds charged with felony offenses

A PDF version of this Fact Sheet is available here.

Background

Effective Jan. 1, 2010, Public Act 095-1031 provided that 17-year-olds charged with misdemeanors be tried in juvenile court, instead of adult court. By raising the age of juvenile court jurisdiction for misdemeanors from age 16 to age 17, these misdemeanants had access to more rehabilitative services and the age range for juvenile court in Illinois came into conformity with most other states. However, Illinois became the only state to place misdemeanant 17-year-olds in the juvenile system while trying all 17-year-olds charged with felonies as adults. The legislation also mandated the state study the impact of the new law and make recommendations for raising the juvenile court age to 17 for felony charges. Public Act 096-1199 directed the Illinois Juvenile Justice Commission to conduct the study. The Commission will describe the state’s first two years’ experience under the law and make recommendations to the Governor and the General Assembly in February 2013.

Overview of Findings

To fulfill this legislative mandate, the Commission conducted legal and social science research, analyzed state and local justice system data, and interviewed practitioners in selected counties. Initial projections that moving 17-year-olds to the juvenile justice system would crowd court dockets, probation caseloads, and detention centers did not come to pass. Although about 18,000 misdemeanor arrests were moved from adult to juvenile court in 2010, the total number of youth in the juvenile system actually dropped due to decreases in overall crime and juvenile arrests, as well as increased use of diversion options. The Commission’s research also revealed that, while the juvenile justice system absorbed the 17-year-olds, the current jurisdictional split between misdemeanors and felonies is unwieldy, especially for law enforcement and court personnel. Most police and prosecutors interviewed by the Commission favor a uniform age of majority.

Recommendation of the Commission

To promote a juvenile justice system focused on public safety, youth rehabilitation, fairness, and fiscal responsibility, Illinois should immediately adopt legislation raising the age of juvenile court jurisdiction to include 17-year-olds charged with felonies.

- Raising the age would bring Illinois into alignment with current legal standards: Most other Illinois laws use 18 as the default age of majority. Today, 38 states set the age of adulthood for criminal matters at 18 and more are considering it. Since 2005, the U.S. Supreme Court has issued a series of rulings which consistently cite neurological and social research demonstrating why 17-year-olds are better-suited to juvenile court than adult court: they are still developing and capable of positive change. In Illinois, this change would mean that about 4,000 17-year-olds annually will be treated just as 16-year-olds are. Raising the age will not change any “transfer” laws, which will allow or require 17-year-olds to be tried as adults for serious offenses.

- Raising the age is the right approach for youth and for public safety: Adult convictions inhibit education and employability, reducing options for success, while youth in juvenile court are at a lower risk to commit future offenses and more likely to become productive members of communities. Studies show that youth who go through the juvenile system are on average 34% less likely to recidivate than if they had gone through the adult system and that 17-year-olds convicted of felony-level offenses are no more likely to reoffend than are 14-year-olds or 16-year-olds. Juvenile court jurisdiction can improve public safety and benefit felony-charged 17-year-olds and local economies.

- The Illinois juvenile justice system can manage the final phase of raising the age: The state’s juvenile justice system is smaller now than it was before it included 17-year-olds. Because of this, many practitioners who were initially concerned about raising the age are now prepared to end the confusing jurisdictional split by accepting felonies. Raising the age will not require new detention or youth incarceration facilities. Moreover, in other states that have raised the age, declining juvenile caseloads and reassignment of personnel from adult to juvenile duties have offset much of the additional expense initially projected.

The future of 17-year-olds in Illinois’ justice system

Legislation signed in 2009 (Public Act 095-1031) provided that 17-year-olds charged with misdemeanors would move from adult to juvenile court jurisdiction effective January 1, 2010. The legislation also mandated the state study the impact of the new law and make recommendations concerning raising the juvenile court age to 17 for felony charges. Subsequent legislation (Public Act 096-1199) directed the Illinois Juvenile Justice Commission to study and present findings to the legislature.

The resulting report, Raising the Age of Juvenile Court Jurisdiction, is available in its entirety here.

The study’s Executive Summary and Recommendations are available here.

The Commission’s Press Release on the report is available here.

The Illinois Youth Reentry and Improvement Law of 2009 directed the Illinois Juvenile Justice Commission to make recommendations for increasing the likelihood that young offenders will succeed after their release from state youth prisons. Before making these recommendations, the Commission conducted a study of how decisions are made in the state’s reentry system, which includes the Department of Juvenile Justice (DJJ), the Prisoner Review Board (PRB), and parole officers with the Department of Corrections.

The Commission is the federally mandated state advisory group to the Governor, the General Assembly and the Illinois Department of Human Services. Appointed by the Governor, the 25 Commission members come from a variety of backgrounds in the juvenile justice field, including law enforcement, locally elected officials, mental health experts, non-profits, delinquency prevention experts and others.

The study concluded that the state’s juvenile reentry system is broken but not beyond repair. The system is intended to help juveniles move from prison cells back to their home communities where they would continue their rehabilitation. In reality, (1) the system does little to prepare youth and families for life outside prison walls; (2) youth on parole rarely receive the needed services or school linkages and too often return to expensive youth prisons due to technical parole violations; and (3) Prisoner Review Board (PRB) parole revocation proceedings are largely perfunctory hearings where the youth’s right to a lawyer and due process are not protected.

Many highly qualified, caring professionals can be found at all stages of the juvenile justice system. However, the system is so structurally flawed that their work is made more difficult and sometimes is even a barrier to successful rehabilitation of the young people and communities they are trying to help.

By instituting a major restructuring of the system, the state could reduce costs, improve public safety, protect the constitutional rights of the juveniles and increase the likelihood that young offenders will become responsible adults.

Unlike adult prisons, youth serve open-ended sentences and can only be released from DJJ by reaching the age of 21, by order of the PRB, or because they served a sentence equal to the maximum sentence an adult would serve for the same offense. Commission members observed 237 PRB hearings and found that parole hearings were rushed, often perfunctory and relied heavily on summary information presented by DJJ. The Commission also reviewed the incarceration, clinical, and parole history of 386 youth whose parole was revoked between December 1, 2009 and May 31, 2010 to determine the extent of screening and services received both inside DJJ and while on parole.

Study Findings and Recommendations

- To make informed decisions about release and to assign appropriate conditions of parole for juveniles, PRB members should receive training needed to perform a comprehensive review of each case and the unique needs of juveniles. The training should include information about adolescent development, the impact trauma on juveniles and the benefits provided by treatment; family dynamics; effective substance abuse treatment; and the range of community-based services available to juveniles upon release from prison.

- The PRB should use specific criteria to make consistent, well-informed release decisions and written decisions should be given to the youth. The criteria should include a determination of whether the youth’s needs would best be met by remaining incarcerated or by receiving rehabilitation in community-based treatment.

- There should be regular PRB reviews of each youth to allow the PRB to document and assess the progress of juveniles. DJJ should establish criteria for determining when a juvenile is ready to be reviewed for release by the PRB; youth should receive a review every six months, instead of the current annual review; youth should be allowed to request a PRB hearing in advance of the youth’s scheduled hearing; and youth should be informed of their rights to request a hearing and be assisted by a legal advocate at each prison.

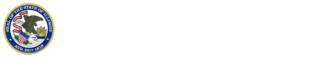

- State statutes mandate a rehabilitative juvenile justice system for juvenile offenders, but parole officers rarely help juveniles obtain schooling, mental health counseling, addiction treatment and employment they need for successful community reentry. Parole agents supervise mixed adult and juvenile caseloads and do not effectively link youth to needed (and often PRB-mandated) services. DJJ has begun to replace the mixed adult/juvenile parole agents with “Aftercare Specialists” in Cook County. Because the newly trained juvenile-only agents should ensure youth receive necessary services upon release and closely monitor youth as they transition back into the community, the Aftercare Specialist program shows great promise and should be instituted statewide.

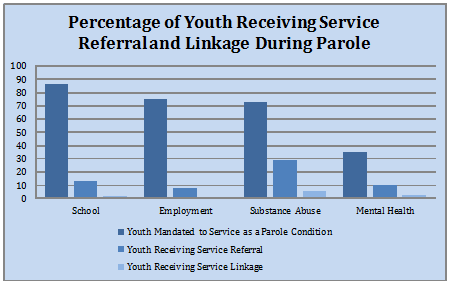

- DJJ should develop youth-appropriate, graduated sanctions for violations of parole conditions and Aftercare Specialists should not rely on returning the youth to prison for technical violations like truancy and curfew violations. Expectations for behavior and the punishment for violations should be explained clearly to the youth and their families.

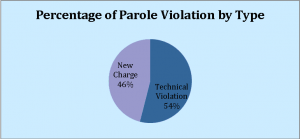

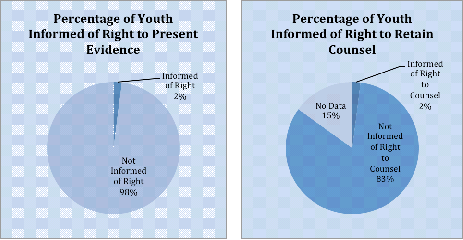

- A judge, rather than the PRB, should preside over parole revocation hearings. Hearings that determine whether a youth may be reincarcerated require judicial oversight to promote fair, uniform, and constitutional due process. Under the U.S. Constitution and Illinois law, youth are entitled to certain rights at parole revocation hearings, including the right to retain counsel and the right to present evidence. However, youth rarely are informed of these rights at PRB hearings; they do not understand revocation hearings; they are not able to present evidence or challenge parole agents, who usually are not present; and most of the youth don’t even have family members present.

- Illinois youth routinely remain on parole until their 21st birthday. Excessive time on parole only increases the likelihood of costly reincarceration for technical violations and does little to enhance their successful reintegration into the community. The length of parole should be limited by law.

- Because DJJ’s information technology is piecemeal, limited and sometimes has outdated information, DJJ has difficulty creating a case management system for each youth and evaluating data to make adjustments and improvements throughout the system. A system-wide data collection and monitoring of youth should be maintained to promote more efficient, effective measurement of individual youth progress as well as system outcomes, ensuring DJJ fiscal accountability and increased public safety.

This proposal can save Illinois at least $79,500 per youth in DJJ per year. In FY 10, it cost taxpayers $86,861 to incarcerate each youth annually, but an effective community-based treatment program, as recommended in the report, would cost between $3,200 and $7.280 per year.

More individualized rehabilitative treatment plans will reduce the likelihood that youth will commit new and more serious offenses – improving the safety of our communities at a lower cost than the current ineffective system.

A PDF version of this fact sheet is available here.

The Youth Reentry Improvement report may be downloaded here.